Making Sweatshops Great Again

Does Trump want us to manufacture sneakers, not semiconductors?

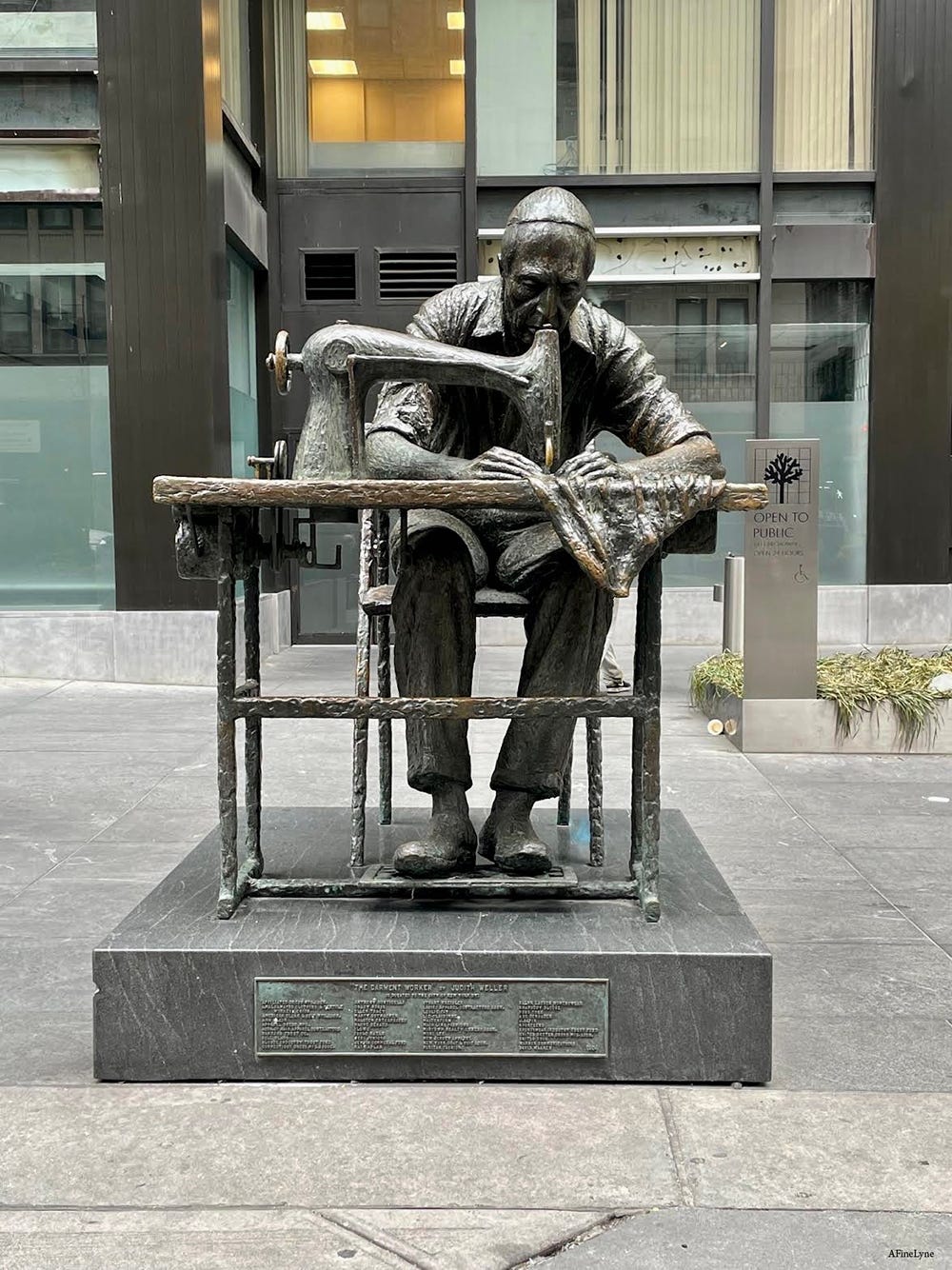

On Manhattan’s 7th Avenue, near the corner of 39th St., there’s a larger-than-life statue of a garment worker — a man wearing a skullcap, hunched over a sewing machine. The statue is a tribute to the locale’s history: It stands in the middle of what’s still called the Garment District. After all, in 1950 New York’s apparel industry employed 340,000 workers.

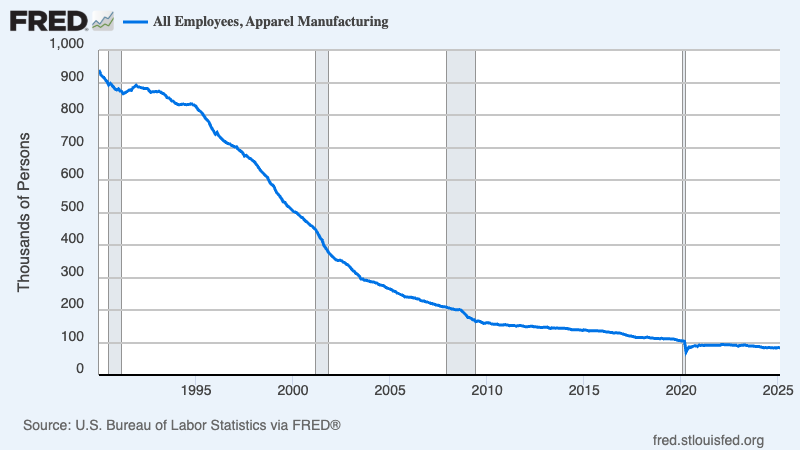

That industry is gone now, not just from midtown Manhattan but from the United States as a whole, having moved to low-wage countries like China and, increasingly, Bangladesh:

No serious person mourns the offshoring of apparel employment. Clothing production is a low-tech industry that even in its heyday mostly employed immigrants who, despite being represented by a powerful union, were paid low wages and often faced harsh working conditions. For a poor nation like Bangladesh, apparel jobs are a big step up from the alternatives. But American workers have better, and better-paying, things to do.

As I said, no serious person wants the apparel industry to come back. But Donald Trump’s economic team aren’t serious people. Last week Howard Lutnick, the commerce secretary, went on CNBC to declare that Trump’s tariffs will bring back U.S. production of t-shirts, sneakers and towels:

His hosts started laughing, but there’s no reason to believe that either he or his boss get the joke. And their nostalgia for industries of the past seems to be matched by surprising hostility toward industries of the future.

Now, the Trumpist view of international trade pretty much begins and ends with the view that whenever Americans buy something made abroad, no matter how much cheaper it may be to import a good rather than try to produce it domestically, that’s a win for foreigners and a loss for America.

I mean, he has slapped high tariffs on Canadian aluminum, which is cheap because smelting uses lots of electricity, and Canada has abundant hydropower. And aluminum is important for U.S. manufacturing. Yet Trump somehow thinks Canada is exploiting us by offering us a key industrial input at a good price.

But back to t-shirts and sneakers. We definitely shouldn’t be making those for ourselves. But what should we be making instead?

A free trade purist would answer, whatever the market decides; let private firms figure out what’s profitable to make in America. And even if you aren’t a free trade purist, you have to admit that governments don’t have a great record of picking winners.

Yet I, like many economists, have come around to the view that we should engage in a limited amount of industrial policy, using subsidies and other tools to promote some industries of the future, especially those involving advanced technology.

There are two big reasons limited industrial policy is back in vogue.

One is that it has become increasingly clear that there are important positive spillovers between technology firms. Silicon Valley is more than the sum of the individual companies located south of San Francisco; it’s a kind of industrial ecosystem of shared services, a pool of skilled workers, and exchange of knowledge. If we want America to be competitive in high tech, we need government policies to encourage the formation of these industrial ecosystems.

The other, grimmer reason we need industrial policy is geopolitics. Circa, say, 2010 not many people worried about how much of the world’s production of advanced semiconductors — which are now crucial to almost everything — was concentrated in Taiwan. Now we know that the age of large-scale warfare isn’t over, and it’s dangerous to rely for crucial products on industrial clusters easily threatened by potential adversaries.

These realizations lay behind one of the Biden administration’s two major pieces of industrial policy legislation, the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, designed to encourage production of semiconductors and expand the broader ecosystem surrounding that production.

Unlike the Inflation Reduction Act, which sought to use industrial policy to fight climate change, the CHIPS Act had substantial bipartisan support; even in an era of intense partisanship, a significant number of Republicans were willing to back an effort to retain America’s technology edge while heading off potential Chinese blackmail. And the act’s subsidies have already shown substantial results, with more semiconductor plants opening on U.S. soil.

But during his speech to Congress last week, Trump veered off into a demand that Congress repeal that act, which he called a “horrible, horrible thing.”

It’s not at all clear what he has against the act, although according to the New York Times many semiconductor companies attribute his hostility simply to “personal animus” toward former President Biden. And given the way the Musk/Trump administration has been behaving, companies aren’t just worried that future contracts will be canceled; they’re worried that the government may renege on contracts it has already signed, and maybe even try to claw back money it has already spent.

As you might imagine, all of this will have a chilling effect on U.S. technology development even if Trump doesn’t manage to repeal the act.

So what do you get if you put Lutnick’s remarks and Trump’s diatribe together? You get a picture of an administration that wants to use tariffs to bring back the low-wage, low-technology industries of the past, while killing policies promoting the industries of the future. Apparently they envision an America that produces sneakers, but doesn’t produce semiconductors.

MAGA!

MUSICAL CODA

As a country moves up the value chain, by focusing on hi-tech and leaving the lo-tech to other countries that still find it attractive, there is a possibility that some of the population will not be able to catch on the train. Subsidies for such left-behind industries, and social security in general, is the mechanism to provide a safety net. Unfortunately the current ruling elites see these safety nets as unnecessary handouts that is impoverishing them! And want to abolish them. People tend to forget why we live as communities in the first place.

I remember graduate school in the late 70s, during the Iran crisis. A brilliant professor (in hindsight) said two memorable things that I think of to this day. One was that in order to understand Iran, one has to understand the United States, for they are much closer in nature than they appear, both captive to religious extremists. Second, he said that the role of capitalism as it was set up was to feudalize us, to make us all serfs. Oh, how we laughed!