China’s Very Bad, No Good Trillion-Dollar Trade Surplus

It’s a sign of weakness, not strength, but a problem for everyone

Not about Trump, and fairly wonky. You have been warned.

Last year China ran history’s first trillion-dollar trade surplus. Here’s one of the many charts circulating, this one from Bloomberg:

Should China be celebrating its achievement? No — this surplus is a sign of weakness, not strength, a symptom of China’s apparent inability to grapple with its fundamental economic problems.

But China’s trading partners won’t be celebrating either. Giant Chinese trade surpluses create problems in other countries too — although not the problems crude mercantilists like Donald Trump imagine. And China’s attempt to export its problems (for that’s what this amounts to) will meet a protectionist backlash; in fact, this would have happened even if Trump weren’t about to take office.

First things first: When a nation runs a trade surplus, what it that telling us? Many people, Trump obviously among them, think such a surplus is a sign of national strength — if you’re selling more to other countries than you’re buying, that must be because you’re outcompeting them. But that isn’t at all how it works.

For a nation’s balance of payments always balances. That is (with some slight technical adjustments),

Trade balance + Net inflows of capital = 0

I often run into people who believe that a successful economy, one achieving rapid productivity growth and leading in cutting-edge technology, will both run big trade surpluses because it’s so competitive and attract lots of foreign capital because it’s such a good investment. But that’s arithmetically impossible.

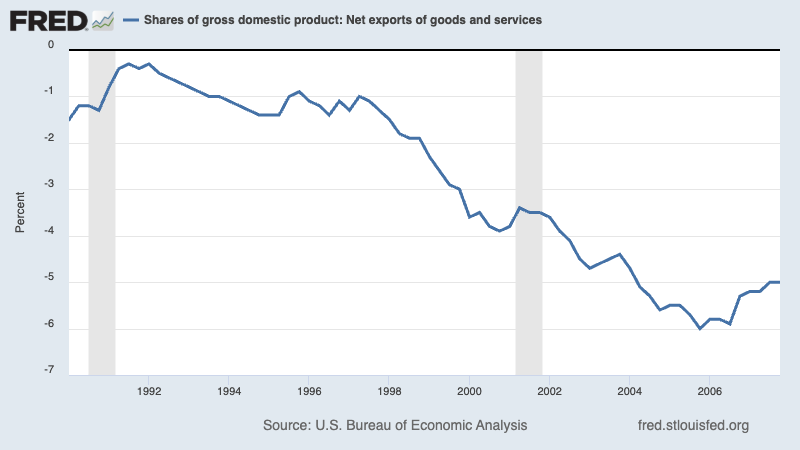

In fact, when an economy surges past its rivals in productivity and technology, it usually does attract a lot of foreign investment — but that means that it runs a trade deficit, not a surplus. A case in point: U.S. productivity surged past productivity in Europe after around 1995, because we were quicker to take advantage of information technology. As a result, foreign money began flooding in — and that led to a much bigger U.S. trade deficit:

Conversely, when nations experience big declines in trade deficits or increases in trade surpluses, it’s usually because something bad has happened. Look at what happened to current accounts (a broad definition of the trade balance) in southern Europe during the euro crisis 15 years ago:

Obviously Greece, Portugal and Spain didn’t experience huge gains in competitiveness. What happened instead was a “sudden stop” — an abrupt cessation of capital inflows when investors lost confidence in these nations’ ability to repay their debts. This forced a drastic decline in imports, largely achieved via austerity policies that pushed these countries into very deep recessions.

Fortunately, China isn’t in that kind of trouble. But as I wrote a couple of weeks ago, the Chinese economy is having big problems adjusting to the prospect of slower economic growth; extremely high rates of investment are no longer sustainable in the face of diminishing returns, yet the government remains unwilling to do the obvious, and promote higher consumer spending.

Running big trade surpluses is one way to compensate for weak domestic demand. And China has been promoting big trade surpluses by weakening the value of its currency (“real” means adjusted for international differences in inflation, “effective” means that we’re looking at a weighted average of exchange rates against China’s trading partners):

Without question, China’s big trade surplus is helping to keep its economy afloat — for now. But the weak yuan policy is almost certain to backfire, big time, because the rest of the world won’t accept those surpluses for very long.

Why not? Trump and his followers argue that when evil foreigners like the Chinese or the Canadians run trade surpluses with America, they’re somehow stealing from us, but that’s an incoherent argument. In fact, there’s a perfectly valid argument to the effect that China is actually doing other nations a favor by selling useful stuff cheap, that China’s trade surplus makes America as a whole (and Europe as a whole) richer.

But that argument won’t fly politically, for very good reasons; what is this “America as a whole” of which you speak?

Consider the so-called “China shock” — or maybe we should call it the first China shock — created by surging imports from China beginning in the late 1990s. These imports displaced 1-2 million manufacturing jobs, but that’s not a huge number in an economy as big and dynamic as ours; in the normal course of events around 2 million workers are fired every month.

But as an influential paper by Autor, Dorn and Hanson showed, these job displacements weren’t spread evenly across America. They were, instead, concentrated in a relatively small number of places, and had a devastating effect on some communities.

My favorite example is the furniture industry, in which employment fell by around 300,000, or 45 percent, in the 2000s, largely because of imports from China. That’s not a large number in a 150-million-worker economy. But furniture manufacturing was concentrated in the North Carolina piedmont. For example, roughly one in every six workers in the Hickory-Lenoir-Morgantown metropolitan area was employed by the furniture industry, and many other jobs were indirectly supported by that industry. So Chinese imports hit that community hard.

A naïve economist would say that if imports increase overall national income, which they usually do, there’s a simple answer: have the winners compensate the losers, and everyone gains. But there are two big problems with that argument. First, it never happens — in practice, the winners don’t compensate the losers. Second, money can’t compensate for the loss of community in places hard hit by foreign competition.

A more sophisticated argument would be that the economy is always changing, with imports only one of many forces that can undermine regional industries; changing fashion, not globalization, destroyed the detachable collars and cuffs industry of Troy, New York. And we can’t prevent change.

As a practical matter, however, regional job loss in the face of import surges generates a powerful political backlash. So the rest of the world just isn’t going to accept China’s attempt to export its way out of policy failure. Trump would probably slap high tariffs on China no matter what, but that giant trade surplus means that Europe, the UK, and probably everyone else will do the same.

Am I saying that Trump is right? No. Tariffs on China are unavoidable unless China makes major policy changes, but the tariffs should be smart and reflect real policy concerns, not a visceral belief that trade deficits mean you’re losing. Also, even given what I’ve said, 60 percent tariffs are wildly excessive. And since China’s trade surplus is a global concern, we should be acting in concert with our allies, not alienating Europe, Canada and Mexico with tariffs on everyone. Among other things, let’s not forget that Trump basically wimped out on China last time after the Chinese retaliated against U.S. farm exports; that would be much less likely to happen if America was working with its allies, not against them.

But while the response to China’s trillion-dollar surplus could and should be much smarter than I fear it will be, that surplus is bad news for China and a problem for everyone else. It’s a sign of inability to grapple with the nation’s problems, and it won’t provide economic relief for very long.

MUSICAL CODA

A song about globalization? Maybe not, but who cares?

I actually followed that really clearly thanks to your cogent explanations. Wonksh perhaps, but the tie-ins to politics and affected communities brought it off the Econ textbook and into the real world.

Another good post by Krugman.

On a thumbnail, what he is saying is that cheap Chinese goods accrue to our benefit. The way to respond is not with a tariff policy that is too high and un-targeted, alienating friend and for alike.

Internally in the US, cheap Chinese imports normally only hurt a very specific industry, often in a very specific geographic area. In the past, the furniture industry in North Carolina (also Grand Rapids, MI and Gardner, MA). That impact is devastating.

Alas, the US lets winners keep windfall profits and does not aide hard hit areas (Rust Belt). Trump did respond with huge subsidies when China targeted farmers, driving down their revenues.m, adding to the deficit along with billionaire tax breaks.

All roads lead back to income and wealth inequality in the US. If we taxed wealth and windfall profits (like we did from the 1940s through the 1970s) we could both benefit from low-cost imports and have the internal financial resources to take care of those financially and socially dislocated.

This is not a hard sell. It’s hard to implement because the wealthy own all three branches of government and the GOP keeps pretending social programs are responsible for the Nation’s Debt, expecting it can force cuts to government spending.

Bernie was right, but he looked crazy with the pointed-finger rants. We need Mr. Rogers making everyone comfortable with the truth and the solution.