A Balance of Payments Primer, Part I

And why you shouldn’t panic over trade deficits

Modern economics was born in Edinburgh, Scotland in the 18th century. You may think I’m talking about Adam Smith and The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776. But while I certainly don’t want to minimize that book’s influence, the fact is that the first exposition of something that today’s economists recognize as a model came some years earlier. It was an essay, “Of the balance of trade,” published in 1752 by Smith’s friend, the philosopher David Hume,

At that time international trade policy was dominated by “mercantilism” — the belief that trade deficits were bad because they drained deficit countries of gold and silver, which accrued to surplus countries. In an era in which transactions were made using gold and silver coins, there was a widespread fear that a country could literally run out of money. Hence trade deficits could be disastrous.

Hume, on the other hand, urged everyone to chill. OK, that wasn’t exactly the language he used. Yet his reasoning was quite chill: according to Hume, a government concerned about trade deficits “may safely trust to the course of human affairs, without fear or jealousy.” Decades before Smith introduced the phrase “invisible hand”, Hume argued that trade imbalances would be self-correcting. In other words, persistent trade deficits would eventually be remedied by market forces. You can read about his argument here.

World trade has changed radically since 1752. We don’t use metallic money to make transactions anymore. Moreover, nations now engage in extensive, large-scale trade in physical and financial assets as well as goods. As a result, persistent capital inflows — that is, inflows of funds from residents of other nations who are investing in your country – have led in some cases to persistent trade deficits. This has been true for the United States since 1980. As examples of these capital inflows, think of European, Japanese and Korean automakers who have invested in manufacturing plants in the U.S. Or Chinese buyers of U.S. government bonds.

But despite the vast changes in the world economy, Hume’s admonition against being obsessed with trade deficits or the balance of payments in general is still good advice.

Yet in America we now have a president who is obsessed with trade imbalances, and his administration has found economists willing to provide arguments to indulge that obsession. I made the case a few days ago that no one should believe that these economists have any real influence. Their arguments are being used the way a drunkard uses a lamppost, for support rather than illumination.

Still, those arguments are out there, and a number of readers have asked me to provide a balance of payments primer, both for general understanding and to give a sense of where there is room for rational disagreement.

I was going to talk about the role of the dollar as a reserve currency, and how that plays into the story. But this post was already getting too long and intricate, so that will have to be a follow-up post, probably next weekend.

Beyond the paywall I’ll discuss the following:

1. How the balance of payments works, and why net capital inflows necessarily imply trade deficits

2. How America became a deficit nation

Balance of payments essentials

All economic transactions involve someone exchanging an asset for something else — in effect someone sells an asset in return for a good, a service, or another asset. You may say that we normally buy things with money — but money, which in the modern world usually consists not of physical currency but of ones and zeroes on a server somewhere, is just a kind of asset. Say I want to buy a Tesla. If I take out a loan to buy a Tesla, I am selling an asset — my loan which is an asset owned by the car loan company — in exchange for a car. If I withdraw funds from my money market account to buy Tesla stock, I’m selling one asset to purchase another asset. In both scenarios, every purchase by me is also a sale by the seller. It’s just accounting.

I personally wouldn’t do either of these things. Elon Musk is reportedly talking about getting into the restaurant business, and I’m already hearing jokes about the Cyberburger, which randomly falls apart or bursts into flame. But you get the idea.

The same principle applies to the transactions a nation does with the rest of the world. Or as we sometimes say, the balance of payments always balances. Every purchase by one country is also a sale for another country, regardless of the form of the exchange. It could be (1) goods and services exchanged for goods and services; or (2) goods and services exchanged for assets; or (3) assets exchanged for assets. The form doesn’t matter: every purchase involves a corresponding sale.

So for the nation as a whole, we have an accounting identity for international transactions:

Sales of domestic goods and services to foreigners + Sales of domestic assets to foreigners = Domestic purchases of foreign goods and services + Domestic purchases of foreign assets

If we took a highly simplified example, in which the only two countries in the world are the U.S. and China, we might say that:

Sales of US wheat to China + Sales of US Treasury bills to China = US purchases of Shein clothing + US purchases of Chinese stocks

OK, writing “goods and services” over and over again would get tedious, so from now on I’m just going to write “goods” with the “and services” implied unless otherwise specified. Also, “services” should be understood to include things like interest payments and dividends, which are in effect payments for the use of someone else’s capital.

With this language simplification, we can rearrange the accounting identity of international transactions to arrive at this:

Sales of assets – Purchases of assets = Purchases of goods – Sales of goods

Applied to the U.S., the left side of this equation is our net capital inflows -- the excess of foreigners’ investment in US assets over our investment in foreign assets. The right side of the equation is our trade deficit – the excess of our purchases of foreign goods over foreign purchases of American goods. Hence:

Net capital inflows into the U.S. = U.S. trade deficit

How this accounting identity is broken down across flows of goods and flows of assets is called a country’s balance of payments. What does the U.S. balance of payments look like in practice? Here’s a snapshot in 2024:

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis

The stacked bar on the left shows U.S. sales to other countries, the bar on the right U.S. purchases from other countries. The two bars are approximately the same height: As I said, the balance of payments always balances. As you can see, the U.S. ran a trade deficit in 2024: U.S. sales of goods (blue) were less than purchases. This difference was offset by a U.S. surplus in sales of assets (orange).

Now, the two stacked bars aren’t exactly the same height. There are some technical issues you don’t want to know about, and there’s also always a statistical discrepancy because data collection isn’t perfect. But the picture is clear. Last year the United States ran a trade deficit — we bought more goods from the rest of the world than we sold — matched by capital inflows — foreigners invested more in America than Americans invested abroad. And this has been our normal situation since the early 1980s.

Why has the US run persistent trade deficits? The accounting identity doesn’t give a clear answer because it cannot reveal what causes what. Do we have a trade deficit because we have a highly innovative economy that attracts foreign investment? or do we have to borrow from foreigners because we have a trade deficit?

In the modern world economists generally subscribe to the former explanation: foreign capital flows, seeking higher rates of return in the US, have driven the US trade deficit. The underlying mechanism runs through the value of the dollar. It looks like this:

1. Foreigners want to invest in America

2. To do so foreigners must acquire dollars

3. Foreign demand for dollars drives the dollar up relative to other currencies

4. The higher value of the dollar relative to other currencies makes U.S. production more expensive and less competitive compared to foreign production

5. The end result is a U.S. trade deficit

How we became a deficit nation

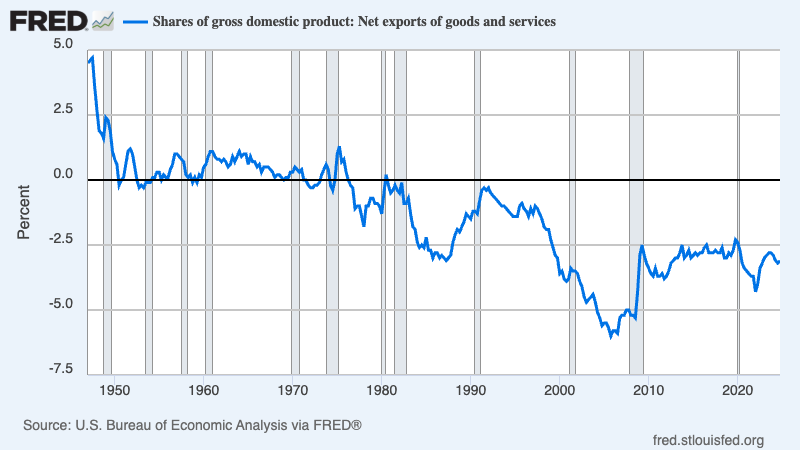

From the end of World War II until around 1980 the United States actually normally ran small trade surpluses:

Those big surpluses at the beginning reflect European nations spending the aid we gave them under the Marshall Plan.

Why were the surpluses small? Because most countries had controls limiting international private capital flows. True, there were exceptions. In particular, U.S. corporations were more or less free to export capital to expand their overseas subsidiaries. Does anyone still remember the 1967 best-seller Le Défi américain by Jean-Jacques Servan-Schreiber, in which he warned that U.S. multinationals were turning Europe into an American colony?

So why did we begin running large, persistent trade deficits after around 1980? Because private capital stopped flowing out of the United States and began flowing in instead. The primary reason was Reaganomics: Ronald Reagan cut taxes while increasing military spending. Reagan had his own coterie of economists, notably Arthur Laffer, who told him what he wanted to hear – that tax cuts would pay for themselves. When this didn’t happen the resulting budget deficits drove up interest rates. This in turn precipitated foreign capital inflows, driving up the dollar and resulting in a trade deficit. So if you want someone to blame for America becoming a deficit nation, lay it on Reagan.

Since the 1990s the story behind US trade deficits has been different: capital inflows have mostly reflected the fact that the United States offers better investment opportunities than other advanced economies. As the Draghi report points out, European productivity growth has lagged the U.S. since the 90s. America has also had more favorable demography — higher fertility and immigration have kept our working-age population growing even as it declines in other advanced countries. Again, this draws in foreign capital by creating investment opportunities, which ultimately means a bigger trade deficit.

I can’t help pointing out that the Trump administration, with its wars on science and education and its new-found habit of arresting and deporting foreigners who come here simply because they are believed to hold anti-Trump views, is making America a much less attractive place to invest. And that, I guess, is one way to weaken the dollar and reduce the trade deficit.

But is the trade deficit a problem? Some economists argue that it is, that U.S. trade is distorted by the dollar’s role as the world’s principal reserve currency, which creates an artificial demand for US assets. As I wrote the other day, there’s no reason to believe that these arguments are actually affecting U.S. policy. To the extent that those promoting these views play a role in the Trump administration, it’s as beards — people who provide sophisticated-sounding intellectual cover for what Trump was going to do anyway.

As it happens, I also believe that these arguments are mostly wrong. But this post is already too long, so check in next week for an explanation.

Dr. Krugman, Good clear explanation. I’m convinced you had to be a really good teacher with lucky students who would walk out of one of your lectures delighted that they now understood a complex economic theory that they had not understood previously. Clear explanations of complex things are not easy to do, and you continue to do those explanations well. Thank you for not just taking up golf or bird watching when you left the Times but instead exploring SubStack. Now, not just your young students benefit from your expertise and writing skills. We all enjoy your posts and learn something from the enjoyment. Stick with it.

Von trump does not understand much but he knows how to cheat, lie and become richer and richer. He does not care for people at all. They are slaves / cows to be milked. Like Pascal Lamy (previous head of world trade organisation) mentioned a few days ago: tariffs war is medieval and idiotic. How long you will keep this convict corrupt traitor president/dictator? Get rid of him pdq!