Today’s post will be short, because I’m on the road — actually at a conference in Belgium — with very little free time. But I thought I might weigh in to support and enlarge upon an exceptionally clear post by the always very good Adam Tooze about the commentariat’s sanewashing of Trumpian economic policy. I especially enjoyed seeing the normally calm Tooze come across as a bit angry.

What got Tooze going were multiple news analyses that tried to portray the vague concept of a “Mar-a-Lago Accord,” an attempt by the U.S. government to restructure the world financial system supposedly to its advantage, as reflecting a serious rethinking of international economic policy. If the plan, or maybe concept of a plan, or whatever doesn’t seem to make sense, that must be because Trump officials are playing some kind of deep game.

But why would you think that? Everything we know about the Trumpists’ approach to economic policy, or policy in general, suggests both that Trump himself has no understanding of economics — that he has prejudices rather than ideas — and that he surrounds himself with people who cater to his prejudices, that as Tooze puts it, the policy visions we’re getting from Trumpland have more in common with

a facelift pandering to the ignorant vanity of an old man than with economic policy as we have hitherto known it.

Look, I understand that it’s more fun to write an article about the supposed emergence of a new economic philosophy than to write yet another article about how ignorant men are, once again, saying stupid things. And I guess some journalists are uncomfortable at the thought that people with great power to shape policy have no idea (or rather nothing but false ideas) what they’re doing.

But trying to put an intellectual gloss on Trumpist international economic policy is sanewashing that misinforms readers rather than helping their understanding.

We actually know what Trump and the people around him — people selected because they agreed, or pretended to agree, with his prejudices — believe about international economic policy. Before Trump first took office, Wilbur Ross and Peter Navarro — who is still, as far as we can tell, the single most influential figure setting trade policy — put out a “white paper” centered on one simple fallacy. This was the claim that you can take this:

GDP = Domestic spending + Net exports

which is just an accounting identity, and conclude from it that trade deficits (negative net exports) shrink the economy. Why not say, instead, that they permit higher spending? In particular, since the trade deficit is equal to net inflows of capital from abroad — another accounting identity — why not see trade deficits as permitting higher investment and increasing growth over time?

But Navarro’s bad economics supported Trump’s crude mercantilist prejudices, which is why he was hired in the first place. And there’s no indication that Trump’s views have become any more sophisticated since then. He has repeatedly claimed that the bilateral imbalance in trade between the United States and Canada — an imbalance that he persistently overstates by a factor of three — means that we’re “subsidizing” Canada, which is straight out of Ross-Navarro. And Trump takes this nonsense seriously enough that he has become obsessed with the idea of a forced annexation of our neighbor and ally.

So yes, Stephen Miran, now the chairman of the Council of Economic advisers, himself wrote a white paper last fall about international finance that isn’t quite as crudely fallacious as Ross-Navarro. And this paper could be construed as lending some intellectual support to Trump’s tariff policy as a tool to force other countries to change their currency policies. This, presumably, is why Miran was hired.

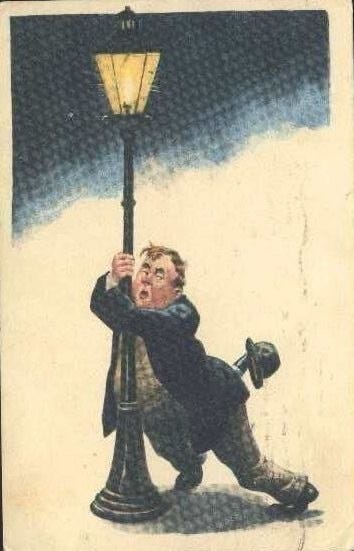

But there’s no reason to believe that Miran’s views (which are muddled, but never mind) are actually influencing policy. Surely Trump’s team is using analyses like Miran’s, as the old saying goes, the way a drunkard uses a lamppost — for support, not illumination.

If you’re still determined to imagine that there’s some serious thinking behind Trump’s international economic policy, consider his views on other policy questions, like crime. After a bump during the pandemic, violent crime in major American cities has fallen back to historically very low levels. New York, for example, had 83 percent fewer murders last year than it did in 1990. Yet Trump insistently portrays our cities as crime-ridden hellscapes where people are afraid to go out. (When I had dinner with friends in Queens last week, my big problems were crowded subways and weaving through the hordes of pedestrians on Roosevelt Avenue.)

Or consider Trump’s continuing endorsement of Elon Musk’s assertion that Social Security checks are going out to millions of dead people — which you might think someone besides the DOGE kids might have noticed.

My point is that Trump believes many blatantly false things that suit his prejudices. Why imagine that he and his courtiers have sophisticated ideas and a deep strategy when it comes to international economics?

On the surface, Trump’s trade policy looks stupid and destructive. Dig deeper, and you discover that this first impression was completely valid. Trying to pretend otherwise is just misinforming readers.

MUSICAL CODA

It’s OK to be silly if you’re self-aware

I love you, Paul Krugman, and I guess that your reasoning and writing are helping many people, such as myself, get through to April 5th, when our numbers can begin to show how many now understand there is a madman in the White House and what are we going to do about it?

Perhaps a better metaphor is the guy who shoots an arrow first and then draws a target around the arrow.