Most Americans who supported Donald Trump probably thought they were voting for lower grocery prices; now he says never mind, let’s seize Greenland instead. Also the Panama Canal and maybe Canada.

I’ve seen various attempts to rationalize Trump’s sudden embrace of what looks like old-fashioned imperialism. A Panamanian hotel has sued the Trump Organization for what it says is tax evasion; Greenland has deposits of rare earths; Canada has poutine. But I think that all of this ascribes too much rationality to Trump’s posturing. I mean, does this sound like someone engaged in sophisticated geopolitics? (No, Chinese soldiers aren’t operating the canal.)

May I say that Trump is still benefiting, maybe more than ever, from media sanewashing? How many Americans, even those who pay attention to the news, know that THIS was the president-elect’s Christmas message?

Anyway, does the Greenland/Panama/Canada thing reflects anything beyond brain worms? Maybe Trump is trying to change the topic after a bad week of setbacks in Congress and a growing sense that he’s being overshadowed by President non-elect Elon Musk. And I do think he believes that engaging in or at least threatening to engage in imperial adventures makes you look strong.

The thing is, once upon a time imperialism was, in fact, a path to power. Brad DeLong has lately been arguing, eloquently, that pre-industrial societies were caught in a Malthusian trap that kept most people mired in deep poverty. The only way an individual could rise above poverty was to be an aristocrat — that is, a member of a predatory gang that used violence or the threat of violence to extract resources from the peasantry. This raw truth could be masked with propaganda tools like high culture and, yes, religion, but it was always about exploitation.

What was true for individuals was also true for states. The only way a state, be it monarchy or republic, could enrich itself was by seizing territory and resources from other states.

But all that changed with the coming of industrialization and globalization. Way back in 1909 Norman Angell published the first edition of his famous and famously misunderstood The Great Illusion. Angell argued that wars of conquest no longer made sense, that they produced no benefit even to the victors. This argument was, however, widely misinterpreted as a prediction that there would be no more wars, which obviously didn’t come to pass.

Angell’s book — which is, to be honest, a fairly heavy slog for modern readers — made two main points. First, in a world economy with substantial trade, nations no longer needed big territories, let alone overseas empires to prosper; he cited the affluence of several small European nations to make his point. Second, even if it conquers a lot of territory, an advanced nation can’t extract enough tribute from its vassals to make a significant difference to its overall wealth.

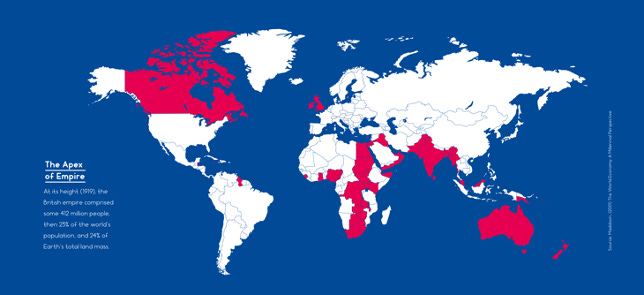

A case in point was the largest of empires. Did the British Empire enrich Britain? Offer (1999) suggests that privileged trading access may have been worth a few points on GDP — or maybe not. Whatever else it may have been, empire wasn’t key to British living standards.

However, few people understood this at the time. Alex Tabarrok quotes an unfortunate passage from George Orwell’s 1937 The Road to Wigan Pier:

…the high standard of life we enjoy in England depends upon our keeping a tight hold on the Empire, particularly the tropical portions of it such as India and Africa. Under the capitalist system, in order that England may live in comparative comfort, a hundred million Indians must live on the verge of starvation–an evil state of affairs, but you acquiesce in it every time you step into a taxi or eat a plate of strawberries and cream. The alternative is to throw the Empire overboard and reduce England to a cold and unimportant little island where we should all have to work very hard and live mainly on herrings and potatoes.

Most of that empire was gone by 1957, when Harold Macmillan asserted that “most of our people have never had it so good.” But he was right.

PS: I like herring and potatoes.

But the real test of Angell’s view came with the biggest war of all.

The Axis powers had multiple motives for starting the war; Hitler, for example, wanted to kill all my relatives who hadn’t moved to America (and, as far as I know, succeeded.) But all three believed that their nations needed empires to thrive. Hitler wanted Lebensraum; Mussolini wanted to restore the Roman Empire; Japan wanted a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Initially, both Germany and Japan succeeded in greatly expanding the territory under their control (Italy not so much.) Germany, in particular, temporarily conquered nations whose prewar GDP was about twice its own, so that on paper the Third Reich ruled an economy comparable in size to that of the United States.

But once America geared up for war, it basically buried Germany under the weight of its superior production of materiel.

Germany, of course, tried to exploit the productive capacity of its empire; indeed, its efforts at extraction were both brutal and desperate, wrecking many of the subject economies. And this resource extraction did contribute to the Nazi war effort, but not nearly as much as you might have expected.

So Angell was basically right. It isn’t literally impossible to extract resources from a conquered nation in the modern world, but it’s hard even if you’re not trying to make the extraction sustainable.

What happened after Axis dreams of empire turned into the nightmare of total defeat? I don’t know whether U.S. policymakers had read Angell, but I suspect some of them had. In any case, America did something unprecedented in the history of warfare. Instead of trying to extract reparations or tribute from our vanquished foes, we helped them get back on their feet.

And the war’s losers did just fine without the empires they thought they needed. Germany had its Wirtschaftswunder. Japanese economic growth astonished the world for 40 years. Italy’s later economic difficulties shouldn’t obscure the fact that by 1970 its GDP per capita was triple its level in 1938.

Which brings us back to Trump . We know that he sees everything as a zero-sum game, with winners and losers; every employed immigrant is a job taken away from native-born Americans, bilateral trade deficits mean that we’re subsidizing foreigners. If he’d been around when Harry Truman and George Marshall decided to help Europe rebuild, he’d probably have called them suckers.

And he almost surely has the atavistic view that conquest makes you stronger. Remember this?

Will he actually try to seize Greenland, Panama and Canada? Probably not, but even threatening to do so makes America seem less and less like a country others can count on for restraint or even sanity.

In fact, Trump’s capriciousness will make America weaker; I highly recommend this essay by Henry Farrell on why.

In any case, aside from an attempt to change the subject, I highly doubt that there’s any real strategy, or even concepts of a strategy, here.

MUSICAL CODA

A cover of Mark Knopfler’s classic by a brilliant bluegrass band from, um, Norway