Why Does U.S. Technology Rule?

Maybe it's just in the right place

And now for something completely — OK, mostly — different. Today’s post isn’t very political. Also, it isn’t one of those discussions about how influential people have basic facts wrong; I’ll do plenty of those, but in this case I’m tackling a serious mystery and offering an answer that could well be wrong.

So, here we go.

One of the things that frustrates those of us who believe that the electorate made a terrible choice last month is that U.S. voters seem to be more or less the only people in the world who believe that America has a bad economy. Other nations look at our performance with envy and even alarm. Indeed, the European Commission recently released a report by Mario Draghi, the former president of the European Central Bank (and the man who saved the euro) calling for urgent action to close the gap.

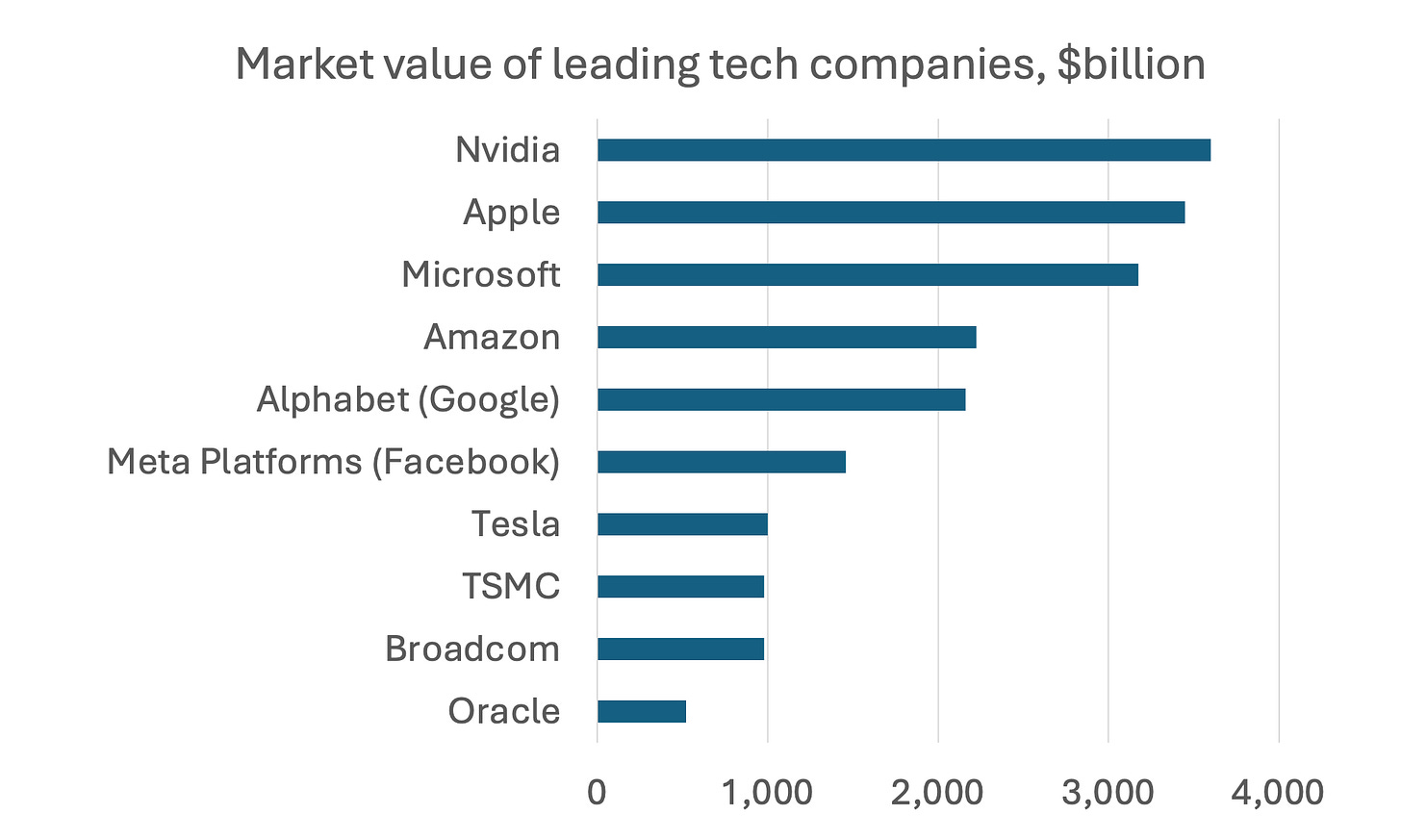

Much of the focus is on U.S. dominance in digital technology. It’s not hard to see why. Look at a list of the ten tech companies with the highest market valuation as of mid-November. With the exception of the Taiwanese semiconductor giant TSMC, all are American; no European company even comes close:

But there’s a funny thing about that list, which goes oddly unmentioned in the Draghi report and every other survey of U.S. tech dominance I’ve read, such as last week’s long read in the Financial Times. It’s true that TSMC aside, all big tech companies are American. But America is a big country, yet our tech giants all come from a small part of that big nation. Six of the companies on the list are based in Silicon Valley — and while Tesla has moved its headquarters to Austin, it was Silicon Valley-based when it made electric cars cool, and the best-known new Tesla product since the Avignon papacy move to Texas has been the Cybertruck:

The other two are based in Seattle, which is sort of a secondary technology cluster.

So what I’m going to do today is offer a heterodox take on U.S. tech dominance. Almost everything I read focuses on things like excessive regulation in Europe, a financial culture that is willing to take risks and so on. I’m not saying that none of this is relevant. But one way to think about technology in a global economy is that development of any particular technology tends to concentrate in a handful of geographical clusters, which have to be somewhere — and when it comes to digital technology these clusters, largely for historical reasons, are in the United States. To oversimplify, maybe we’re not really talking about American tech dominance; we’re talking about Silicon Valley dominance.

To the extent that this is true, I think it has some important implications. These will have to go in another post, because this one is already too long. But in any case, let’s look at the background.

Go back a generation, and the U.S. economy, while huge and powerful, didn’t look all that exceptional. To a first approximation, all advanced countries seemed to be on the same technological level and had roughly the same productivity, that is, output per person-hour. Europe had lower G.D.P. per capita than the United States, but that was because Europeans worked fewer hours, which in turn largely reflected policies mandating that employers provide vacation time, while America was (and is) the no-vacation nation. Europeans had less stuff but more time, and it was certainly possible to argue that they were making the right choice.

Starting around 2000, however, America surged ahead. The Draghi report opens with a chart that puts this relative surge in historical perspective, showing how it partially reversed the great productivity convergence that followed World War II:

So can we explain America’s surge and Europe’s lag? My first thought when opening the Draghi report, which does indeed try both to explain Europe’s lagging performance and to offer recommendations for turning it around was, “Good luck with that.” It’s notoriously difficult to explain or predict differential success by national economies. In 1970 Robert Solow, the father of modern economic growth theory, wrote somewhat snarkily (I learned from the master) about attempts to explain Britain’s sluggish postwar growth:

Every discussion among economists of the relatively slow growth of the British economy compared with the Continental economies ends up in a blaze of amateur sociology. The difference is the bloody-mindedness of the English worker, the slowness of English management to adopt new products or new processes or new ideas, the elaborately amateur character of English business practice, the excessive variety of English goods corresponding to a finely stratified society, or the style of English education and the attitudes it imprints on graduates, or the difference is all of these in unspecified proportions.

“Science and ideology in economics” The Public Interest, Fall 1970

For that matter, I’m old enough to remember the days when airport shops were full of books with samurai warriors on the cover, purporting to teach you the secrets of Japanese management, which would, many confidently predicted, make Japan the world’s dominant economy:

That said, however, explaining the growing US-EU gap may require less amateur sociology than usual, because the gap involves a surprisingly small part of the economy. The Draghi report has a chart decomposing the gap, by industrial sector:

This is not, to be honest, the most easily readable chart ever, but Draghi interprets it as saying that the US-EU divergence is all about digital technology — and not even the use of this technology but its production:

Excluding the main ICT sectors (the manufacturing of computers and electronics and information and communication activities) from the analysis, EU productivity has been broadly at par with the US in the period 2000-2019. The remaining disadvantage in productivity growth versus the US is significantly reduced to 0.2 percentage points (0.8% productivity growth for the US versus 0.6% for the EU). The actual EU-US gap can be considered close to zero as EU 27 productivity growth is 0.2 to 0.3 percentage points higher than the EU10 selection (for which EU KLEMS data is available). For 2013-2019 the role of ICT is even more striking, as the EU productivity growth excluding the main ICT sectors exceeded that of the US by some margin.

So it’s all tech, although the report concedes that “the US also has high productivity growth in professional services and finance and insurance, reflecting strong ICT technology diffusion effects.”

Which brings me to my point: both tech and finance are highly concentrated geographically, for reasons famously explained by Alfred Marshall more than a century ago. His motivating example was the cutlery industry in Sheffield, but the same logic, especially local diffusion of knowledge, applies to tech in Silicon Valley, or finance in Manhattan:

When an industry has thus chosen a locality for itself, it is likely to stay there long: so great are the advantages which people following the same skilled trade get from near neighbourhood to one another. The mysteries of the trade become no mysteries; but are as it were in the air … Good work is rightly appreciated, inventions and improvements in machinery, in processes and the general organization of the business have their merits promptly discussed: if one man starts a new idea, it is taken up by others and combined with suggestions of their own; and thus it becomes the source of further new ideas.

Natural advantages typically play a minor role in the perpetuation of industrial clusters; if soil and climate were what mattered, the Santa Clara valley would still be growing apricots. Instead, industrial clusters often reflect natural advantages that have long since ceased to be relevant, like New York’s position as the terminus of shipping via the Erie Canal. Indeed, they often reflect sheer accident: Seattle is what it is because Bill Gates grew up there. Stanford University played an important role in Silicon Valley’s rise, but it’s unclear whether it would have become what it is if two guys named Hewlett and Packard hadn’t started a business in a garage.

And here’s the thing: industrial clusters supported by information spillovers and other forces can serve world markets, not just domestic demand. Look at world trade in financial services:

Does anyone think that Britain’s outsize role reflects, say, special features of UK culture that make Brits especially good bankers? Of course not. Britain sells a lot of financial services because of the positive spillovers created by the concentration of banking in London, a concentration established when London was the capital of a global empire, but which persists through the dynamics of localized positive externalities (pardon the jargon, but at this point it should be obvious what I mean.)

What I’m suggesting is that America’s tech advantage may bear considerable resemblance to Britain’s banking advantage. That is, it may have less to do with institutions, culture and policy than the fact that for historical reasons the world’s major technology hubs happen to be in the United States, and remain there for the usual Marshallian reasons.

Even things that look like major institutional differences may be downstream from geographical concentration. Europeans lament their lack of a well-developed venture capital sector, ready to take risks on innovation. Indeed, there’s no European equivalent of Sand Hill Road, famous for its venture capital firms. But Sand Hill Road isn’t just a state of mind; it’s an actual place, and it owes its existence in large part to the opportunities offered by Silicon Valley. Venture capitalists are ready to take risks on U.S. tech because geographical proximity makes them better able to judge which risks are worth taking — that is, the mysteries of the trade are no mysteries but are, as it were, in the air.

And high U.S. productivity has a lot to do with very high productivity in tech and finance hubs. The BEA just released county and metro area GDP estimates; these can be combined with BLS data to produce estimates of output per worker in selected regions. As you might guess, GDP per worker is much higher in tech and financial hubs than in the rest of the country:

These high-productivity clusters probably play a large role in high average US productivity.

Now, there are two big further questions here. First, to what extent does high productivity in a few geographical clusters trickle down to the rest of the economy? Second, is there any way Europe can make a dent in these U.S. advantages?

The answer to both questions is, I don’t know. But I’m working on it.

MUSICAL CODA

One reason is that Al Gore was a rare politician with the vision to see the potential and he spent 20 years funding and building markets and legal basis for Internet as a technology and business.

For his troubles, he was transformed into a public joke by our moronic media, especially your former employers at the NYT.

All astute observations. Two more critical factors help explain why Silicon Valley is where it is. This area is home to both Stanford and UC Berkeley - two of the world's top science and engineering universities. Also, California has long banned non-compete agreements, so it was the rare place where employees who had a better idea, but were being held back by their employer, could walk across the street and start a competing company - great for innovation.