The Fraudulence of “Waste, Fraud and Abuse”

History repeats itself, the first time as farce, the second as clown show

First things first: welcome to readers new and old. Now that I have written my last column for the New York Times, this newsletter is coming out of dormancy. It will be mostly economics-related, and I’ll try to stay away from pure political punditry, although everything — including this post — is political these days.

This newsletter will be a lot wonkier than my Times column, and usually wonkier than my old Times newsletter. Definitely snarkier than either. I’ll try to stay fairly accessible, but may at times revert to academic-economist mode.

All posts will be free for a while, although I will eventually set up paid subscriptions for some content.

Short form thoughts will be appearing here. (https://bsky.app/profile/pkrugman.bsky.social)

And with that, let’s get going.

Once upon a time a Republican president, sure that large parts of federal spending were worthless, appointed a commission led by a wealthy businessman to bring a business sensibility to the budget, going through it line by line to identify inefficiency and waste. The commission initially made a big splash, and there were desperate attempts to spin its work as a success. But in the end few people were fooled. Ronald Reagan’s venture, the President's Private Sector Survey on Cost Control — the so-called “Grace commission,” headed by J. Peter Grace — was a flop, making no visible dent in spending.

Why was it a flop? There is, of course, inefficiency and waste in the federal government, as there is in any large organization. But most government spending happens because it delivers something people want, and you can’t make significant cuts without hard choices.

Furthermore, the notion that businessmen have skills that readily translate into managing the government is all wrong. Business and government serve different purposes and require different mindsets.

In any case, the Grace commission’s failure taught everyone serious about the budget, liberal or conservative, an important lesson: Anyone who proposes saving lots of taxpayer money by eliminating “waste, fraud and abuse” should be ignored, because the very use of the phrase shows that they have no idea what they’re talking about.

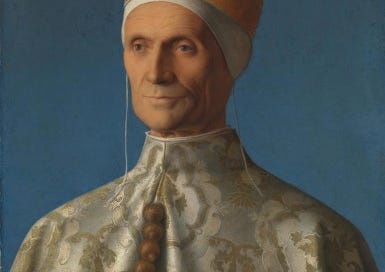

OK, you know where this is going. There’s an obvious parallel between the Grace commission and Donald Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency, DOGE, led by Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy. (The picture above is Leonardo Loredan, doge of Venice from 1501 to 1521, painted by Bellini.) But there are differences too: Muskaswamy bring a level of arrogant ignorance and clownish amateurishness that Grace never came close to emulating.

Grace, after all, assembled a staff of nearly 2,000 business executives divided into 36 task forces, who spent 18 months on the job, although they mostly came up empty. So far, at least, Muskaswamy don’t seem to be doing anything besides credulously scooping up random posts from social media.

Oh, and putting supervision in the hands of Marjorie Taylor Greene won’t help.

That said, there’s a pattern in their pronouncements so far, which I’d describe as Willie Sutton (the man who robbed banks because “that’s where the money is”) in reverse: going where the money isn’t.

One of the first posts on DOGE’s Twitter account (of course it has a Twitter account) makes a classic, maybe the classic rookie error when talking about the federal budget, imagining that foreign aid is a significant expense:

Surveys consistently show that the public believes that foreign aid is around 25 percent of federal spending. But self-proclaimed budget experts should be aware that this is completely wrong; the true number is actually less than 1 percent.

Furthermore, whoever posted that chart didn’t bother to read the label. It’s not a chart of total foreign aid, just humanitarian aid — which is about one-sixth of one percent of federal spending. Overall, by the way, America spends a smaller percentage of GDP on foreign aid than the average advanced nation.

Moving on: In what I guess we should consider their opening manifesto, published in the Wall Street Journal, Muskaswamy call for “mass head-count reductions across the federal bureaucracy.” This suggests that they believe that bloated payrolls are a major budget issue. But how big a factor is employee compensation in federal spending? This big:

Again, going where the money isn’t.

But wait: aren’t there tens of millions of Americans employed by the government? Yes, there are — but they overwhelmingly work for state and especially local governments, not the federal government DOGE is supposed to be tackling. In fact, federal employment is about the same now as it was in the 1950s:

What are all those state and local workers doing? The Census offers a very useful chart:

The lion’s share of state and local employment is in education. Much of the rest is either in hospitals and other health care or in law enforcement. So when someone says “government worker” you shouldn’t imagine a paper-pusher in a cubicle — I mean, the government, like the private sector, does have lots of guys in cubicles, but they aren’t the typical employee. You should instead picture a schoolteacher, or maybe a nurse or a police officer.

But if the federal government doesn’t employ all that many people, why does it spend so much money? The answer — which, again, anyone who has paid the least attention to the subject knows, but Muskaswamy apparently don’t — is that the federal government is basically an insurance company with an army. Nondefense spending is dominated by Medicare, Medicaid and Social Security, with relatively small additional amounts for other safety-net programs like food stamps and health insurance subsidies.

Are these programs efficient? In the case of Social Security, the answer is a flat yes: it simply sends out checks, with very low overhead and very little fraud. (Not zero fraud: a few years ago someone managed to impersonate me and collect checks for a few months. But the Social Security employees who helped me resolve this were incredulous, because this almost never happens.)

Health care is a more complicated story; there are some real inefficiencies in our system. But Musk seems to have the nature of these inefficiencies completely backwards:

Yes, American health care has uniquely high administrative costs. But Musk pretty clearly imagines that these costs reflect government inefficiency, when the real reason health care in America involves so much bureaucracy is the exceptional degree to which we rely on private insurance companies. Comparing administrative expenses for public and private insurance is tricky, but there’s no question that they’re much higher in the private sector.

This comes back to the point that running the government isn’t at all the same as running a business. The purpose of Medicare and Medicaid is to pay for peoples’ health care. The purpose of health insurance companies is to collect premiums; paying for care is a cost — the industry actually calls the share of premiums that end up paying medical bills the “medical loss ratio” — and they devote considerable resources to finding ways to avoid covering medical expenses.

Obligatory disclaimer given recent events: No, I’m not offering a justification for killing health-industry executives. Murder is evil, and in this case it’s also stupid. The problem with the U.S. health insurance industry isn’t that it’s run by bad people, it’s the antisocial incentives created by the system.

Some readers may ask why, if I believe that private health insurance is so problematic, I didn’t support Bernie Sanders’s call for a single-payer system. The answer is political realism; it wasn’t going to happen, while an enhanced Affordable Care Act could and did (and now we’ll see if it survives.)

Back to government-financed health care: Am I saying that all is well with Medicare? No. True, in recent years the program has had remarkable, unheralded success in controlling costs, on a scale orders of magnitude larger than anything Muskaswamy are likely to achieve:

And the Biden administration finally — finally! — gave Medicare the ability to negotiate over drug prices, which is a serious cost saving.

But the program faces a threat of rising costs due to, you guessed it, privatization: a growing number of seniors have bought Medicare Advantage plans, which funnel taxpayer money through private insurance companies, and there’s growing evidence that these plans have become a major source of, well, waste, fraud and abuse. The Wall Street Journal reports $50 billion in outlays for diseases doctors no longer treat. Some estimates suggest that overbilling by Medicare Advantage plans may cost taxpayers more than $100 billion a year; United Healthcare lost a big lawsuit over that practice.

Somehow, though, I very much doubt that DOGE will recommend rolling back Medicare privatization.

Now, in the end none of this may matter. The real purpose of DOGE is, arguably, to give Elon Musk an opportunity to strut around, feeling important. And while it’s a clown show, these clowns — unlike some of the other people Trump may put in office — won’t be in a position to inflict major damage on national security, public health and more.

But it is a clown show, and everyone should treat it as such.

MUSICAL CODA

The Times recently had a piece on Lauren Mayberry of Chvrches. Here’s a clip from their first live performance in 2012; the lyrics seem alarmingly appropriate for this moment:

I was sad when I learned of your retirement from the NYT, as I regularly read your NYT pieces for the last 23 years to help make sense of current events. But I am so glad you are continuing with this newsletter, and I love your plans for it, including your plans for wonkier entries. Thanks so much for continuing to write!

There is an equivalent in municipal government ( am on the finance committee in my town). When you ask property tax payers for an tax increase in my town, opposition will suggest that we live within our means. When we tell them that the alternative is a set of cuts they ask why we are threatening to cut public schools, public safety and public works. When we tell them its because those services represent more than 80% of the budget they ask why we can't cut pension and healthcare costs. Then we tell them the only way to cut those costs is to lay people off and 90% of our employees are in public schools, public safety and public works. Then they get very quiet.