A few days ago the New York Times had a good piece on how the former East Germany is suffering from a demographic doom loop: Young people, especially educated women, have been moving out. Those left behind are depressed; men, presumably, are frustrated; and they’re angry. One result has been strong support for the neo-Nazi Alternative für Deutschland (AfD), which, of course, has been endorsed by Elon Musk and received support from JD Vance.

The article noted that there have been parallel economic and political trends in other advanced countries, including the United States. Indeed, last fall I wrote a newsletter, “The Political Rage of Left-Behind Regions,” making explicit comparisons between East Germany and West Virginia.

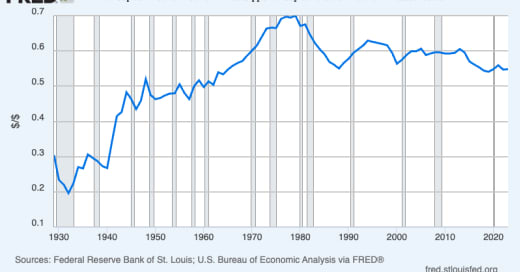

What readers may not know is that while all advanced nations are currently experiencing some version of the kind of regional divergence afflicting East Germany, this is a relatively recent phenomenon. Between the early 20th century and around 1980, the opposite was happening: poorer regions were steadily closing the gap with richer regions.

Then the dynamics reversed. East Germany, America’s eastern heartland, England’s North, rural France, Korea outside Seoul were all to some degree left behind.

Furthermore, we know a fair bit about why this trend reversed (although we don’t have easy answers.) And as it happens, the economics of regional convergence and divergence was one of my research specialties during my academic career.

So I thought I’d devote this weekend’s primer to economic geography. Past the paywall you’ll find:

1. Why economic activity sometimes clumps together, but sometimes spreads out

2. Why did regions begin converging in the early 20th century? Why did they diverge again in the 1980s?

3. Social and political consequences of being left behind

4. Can anything be done for left-behind regions?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Paul Krugman to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.