From Exorbitant Privilege to Invincible Ignorance

Arithmetic has a well-known globalist bias

Perhaps because it can seem mysterious, international monetary economics surprisingly often makes people quotable. Even more often, it makes them say things that are just stupid — but I’ll get there in a bit.

Maybe I’m biased, because it was one of my academic home fields, but it seems to me that international money has had more than its share of memorable tag lines. When Britain went off the gold standard, John Maynard Keynes declared, “There are few Englishmen who do not rejoice at the breaking of our gold fetters.” After the war, whenever speculators began betting against the pound, some British politicians blamed the “gnomes of Zurich,” which was silly — everyone in international finance knew that the relevant gnomes were in Basel.

Perhaps the most durable such coinage, however, was the complaint by Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, Charles de Gaulle’s finance minister, that the international role of the dollar gave the United States “exorbitant privilege” — basically the ability to run persistent trade deficits because the rest of the world had to accept our dollars. (The quote is often misattributed to de Gaulle, who didn’t say it, although it surely reflected his views.) And this claim by Discard Disdain, as The Economist once called him, has been repeated by many people over the years.

As it happens, I’m something of an exorbitant skeptic. I don’t believe that the dollar’s special role provides major economic benefits to the United States. I definitely find myself scratching my head when I see economic commentators claiming that America’s ability to run persistent trade deficits is unique, when a few minutes with IMF data tells you that it ain’t so (the current account is the broad definition of the trade balance, including services and investment income):

It's possible that the dollar’s special role lets America borrow more cheaply than it otherwise would; some theoretical models, like the Gopinath/Stein “dominant currency” story, predict this. But the effect, if it’s there, is too small a signal to extract from the statistical noise.

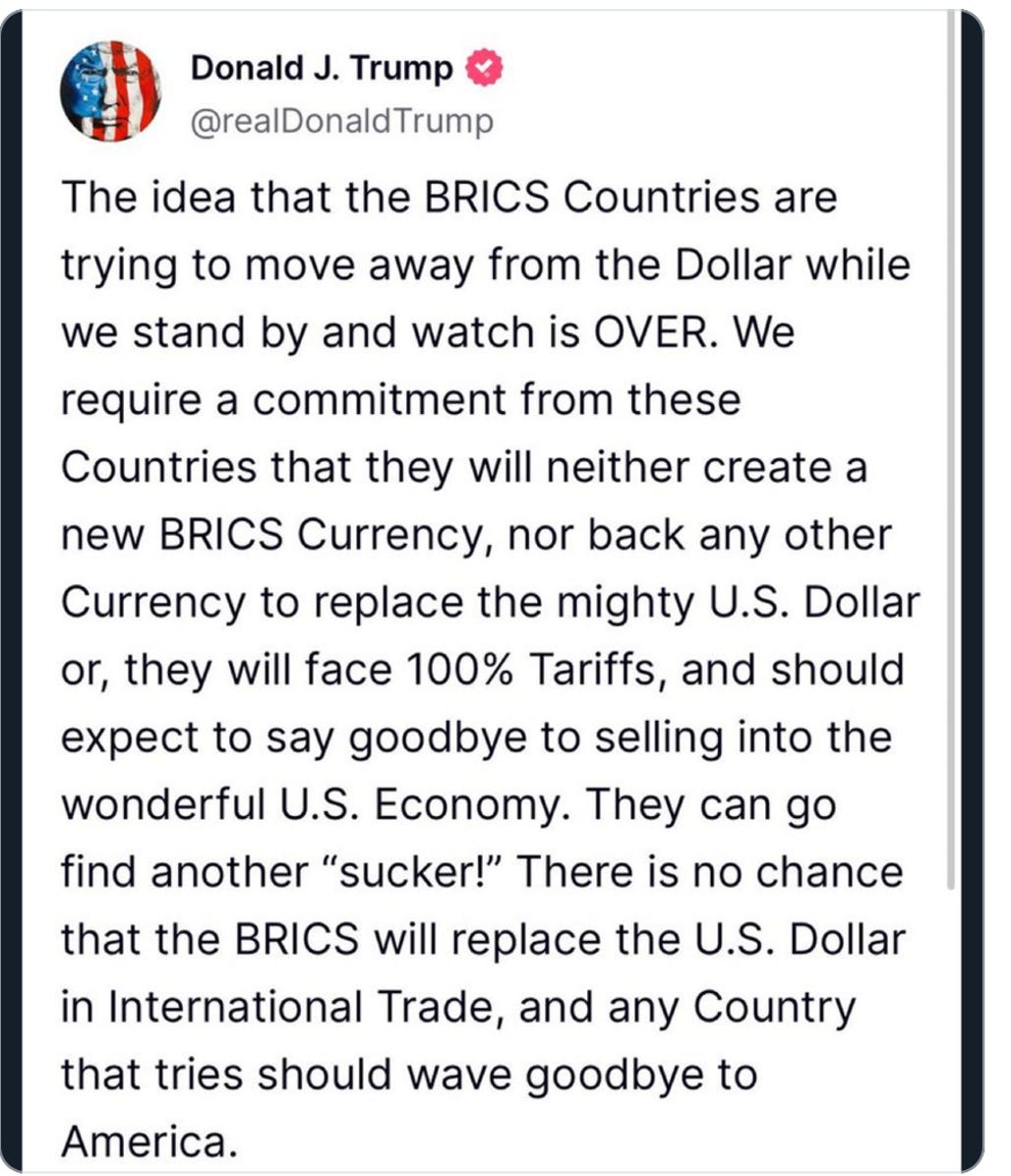

But you know who does believe that the dollar’s dominance is an important source of U.S. power and is making dire threats against anyone trying to replace it? Donald Trump, of course. Here’s his recent rant on Truth Social:

There’s a lot that’s foolish about that rant, starting with the idea that foreign governments can simply replace the dollar by decree (although others, like Vladimir Putin, share the same misconception.) I’ll write a future post about why that’s not at all how it works.

There are also delusions of grandeur: Trump clearly imagines that America holds all the cards when it comes to a possible trade war, and I fear that he and the rest of us will soon get an object lesson in the limits of U.S. trade leverage.

But what’s really bizarre about Trump’s rant is that given his views about trade, he should want to see the dollar lose its special role.

Here’s what you need to know about the balance of payments: it always balances. That is,

Trade balance + Net inflows of capital = 0

(although there are a few asterisks involving investment income; never mind)

What Giscard d’Estaing argued was that because the rest of the world was forced to accept dollar assets, allowing America to run persistent trade deficits, America was in effect being subsidized: We got to consume real goods and services produced abroad, and all they got in return was pieces of paper.

But Trump firmly believes that because we’re running trade deficits with other countries, we are subsidizing them.

Here, for example, is what he said when justifying potential high tariffs on our neighbors:

We're subsidizing Canada to the tune over $100 billion a year. We're subsidizing Mexico for almost $300 billion. We shouldn’t be – why are we subsidizing these countries? If we're going to subsidize them, let them become a state. We're subsidizing Mexico and we're subsidizing Canada and we're subsidizing many countries all over the world.

What? We aren’t subsidizing Canada or Mexico in any normal sense of the word — certainly not in the way poorer U.S. states are in effect subsidized by richer states. What Trump means is that we’re running trade deficits with both countries, although his advisers have come up with some kind of new math to inflate those deficits, which were actually $64 billion and $152 billion last year.

But how does running a trade deficit with Mexico mean that we’re subsidizing our southern neighbor? They’re sending us useful stuff, like auto components. In return, we’re sending them IOUs of some kind, such as federal or corporate debt. Neither side is a victim. What’s he thinking?

Well, probably he isn’t thinking; it’s all visceral. He wants America to be a winner, which means both attracting lots of foreign capital and running trade surpluses. And if anyone tried to tell him that this is arithmetically impossible, he’d probably denounce them as a deep state Marxist pedophile or something.

However, Peter Navarro, Trump’s trade czar, has tried to explain why he thinks trade deficits make America poorer, and his explanation doesn’t try to repeal the laws of arithmetic; it’s just wrong on the facts.

Here’s what Navarro wrote in a 2016 white paper with Wilbur Ross, who later became Secretary of Commerce:

[S]uppose the US had been able to completely eliminate its roughly $500 billion 2015 trade deficit through a combination of increased exports and decreased imports rather than simply closing its borders to trade. This would have resulted in a one-time gain of 3.38 real GDP points and a real GDP growth rate that year of 5.97%.

Where’s that coming from? Every basic economics course teaches students the national income accounting identity:

GDP = C + I + G + NX

where C is consumer spending, I is investment spending, G is government purchases (as opposed to transfers of income like Social Security checks) and NX is net exports — the trade balance. If NX goes up, that is, the trade deficit falls, something else has to adjust. And Navarro simply assumed that it would be GDP, that a smaller trade deficit would lead to higher growth.

But that doesn’t have to happen. In fact, it isn’t even possible unless the economy is deeply depressed to start with, so there’s lots of spare capacity that can be put to work to increase GDP. That’s not normally the case, and when it isn’t, you’d expect changes in the trade balance to be offset by changes in other components of GDP, especially investment.

Let me give you a real-world example of how these things work in practice, in this case involving a big increase rather than a big reduction in the trade deficit. It’s kind of a forgotten episode now, but the U.S. trade balance moved deeply into deficit between the mid-1990s and the mid-2000s:

Did this trade deficit cut into growth? Not at all. The economy boomed in the late 90s, suffered a mild recession when the tech bubble burst, then resumed growth until the housing bubble burst in 2007. In terms of the national accounting identity, the counterpart of NX down wasn’t GDP down, it was I up: first a boom in nonresidential investment (basically business investment) during the tech boom, which handed off to housing during the housing boom:

And then everything went to hell, but that’s another story.

I was careful to say “counterpart,” not “consequence,” because an accounting identity doesn’t tell you anything about causation. In fact, it’s fairly obvious that over this period changes in investment demand were driving the trade balance. First came the boom in business investment — much of which, by the way, involved established telecoms companies rather than flaky dot-coms — which handed off to the housing boom.

How did booming investment lead to a soaring trade deficit? By drawing in lots of foreign money, which drove up the value of the dollar, making U.S. goods less competitive on world markets:

So was America somehow subsidizing other countries by running a trade deficit? I can’t think of any way to make that case. If anyone got taken for a ride it was foreign investors, some of whom bought Pets.com in the 90s and subprime mortgage-backed securities in the 00s.

So, does it matter that Trump is invincibly ignorant about trade, his signature issue? I think so. He imagines that other countries are taking advantage of America and will meekly comply with his demands that they stop; that’s not how they see it, and he’s going to face ugly retaliation — those “subsidized” Canadians are already talking about export taxes on oil and uranium. You’d like to think that when everything goes wrong — when his demands that foreigners both invest in America and stop running trade surpluses aren’t met, because that’s arithmetically impossible — he’ll back off and take advice from the adults in the room. But there won’t be any adults in the room. And I have no idea what comes next.

MUSICAL CODA

Good to see you with the gloves off Paul. It must have been stressful getting pieces past the NYT editors.

"And if anyone tried to tell him that this is arithmetically impossible, he’d probably denounce them as a deep-state Marxist pedophile or something."

Thanks for the laugh, even a nervous one.