Democrats Shouldn’t Support Tariffs

Don't get sucked in by Trump's revenge mania

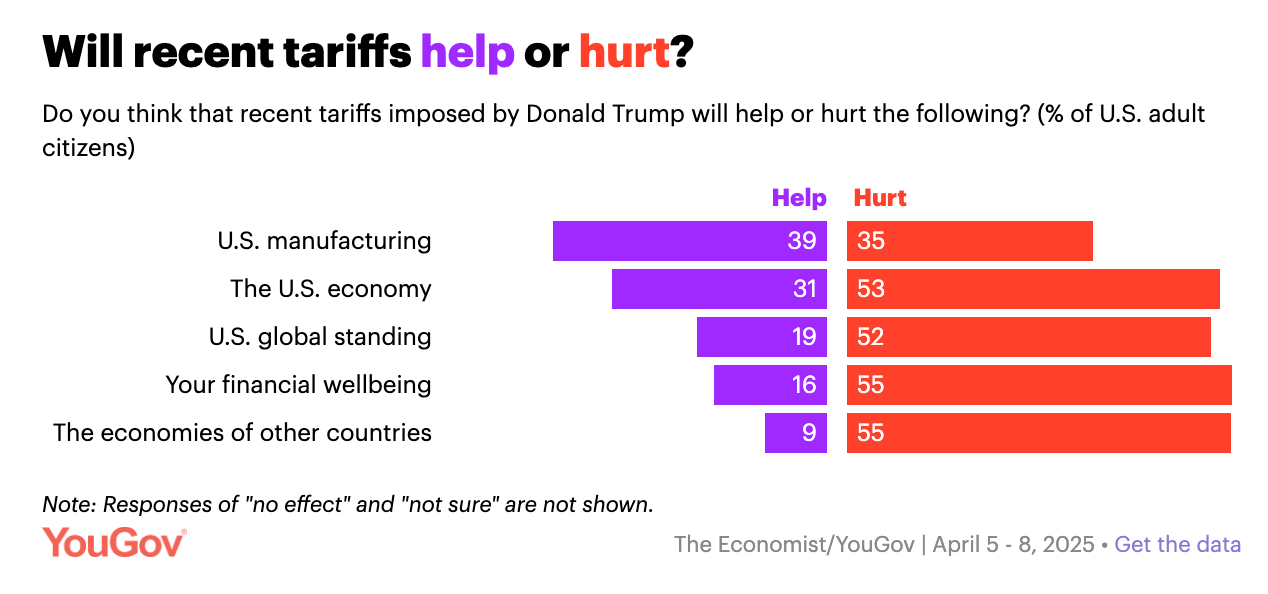

Source: YouGov

Donald Trump’s tariffs are bad economics. They’re also bad politics. I’m not an expert on issue polling, but public opposition to the Trump tariffs looks extraordinary. It’s especially amazing when you bear in mind that many Republicans would support him if he said that the sky was green and all this blue stuff was a deep state conspiracy. Associating yourself with those tariffs in any way is tying yourself to an anchor that has just been thrown overboard.

So Democrats need to stop giving Trump cover. They shouldn’t be saying, as Gretchen Whitmer unfortunately did, that they can understand Trump’s motivation. Similarly, Shawn Fain, president of the United Autoworkers, has done his members a disservice by endorsing Trump’s auto tariffs: Republicans don’t care about helping workers, so all he has done is throw away credibility.

For the reality is that Trump’s motivation for tariffs, as for everything else, seems to be a desire to punish. In this case he wants to punish other countries, which he insists have treated America unfairly. He’s wrong when it comes to our (former?) allies: Europe and Canada, for example, have done nothing wrong. And while we have real grievances against China, Trump’s tariffs are a very bad way to address those grievances, not least because he’s alienating everyone who should be on our side.

But shouldn’t we be trying to restore U.S. manufacturing? Let me make three points:

1. Trump’s tariffs will hurt, not help, manufacturing

2. If you want to promote manufacturing, you should use industrial policy, not tariffs

3. Good jobs don’t have to be in manufacturing, and manufacturing jobs aren’t necessarily good

Trump’s tariffs will hurt U.S. manufacturing

Trump’s tariffs will reduce, not increase, the number of manufacturing jobs in America, for two reasons.

First, U.S. manufacturing relies on imported inputs, from steel to screws, that are becoming much more expensive because of tariffs. The latest twist in tariff plans, the exclusion of electronics announced Saturday, lets final products in free while taxing inputs, actively discouraging U.S. production. Let me repost Joey Politano’s quick summary:

Second, the constant changes in tariffs create huge uncertainty. Who wants to invest in manufacturing production when you have no idea what tariff rates will be a few months down the road? I joked Sunday morning that soon Trump would be changing tariffs every day; a few hours later Howard Lutnick declared that the electronics exemption, announced Saturday, was only temporary, which Trump appeared to confirm with a Truth Social post later in the day. \_(ツ)_/¯

But should we forswear all attempts to help manufacturing? No, but we should do it right.

If you want to promote manufacturing, promote manufacturing

My guess is that few people engaged in current debates over trade policy and manufacturing know that many of the same issues were addressed in the 1960s and 1970s by economists trying to devise economic strategies for what we now call emerging markets. But if they were, they’d know about a clear lesson that emerged from that discussion (see, for example, Max Corden’s Trade Policy and Economic Welfare.) Namely, if you want to promote an economic activity you should promote it as directly as possible.

So if you think manufacturing is important, you should pursue industrial policies, especially subsidies, that specifically boost manufacturing. Tariffs are at best an indirect way to help, with harmful side effects including higher consumer prices and damage to industries that use imported inputs. Tariffs may look less expensive than industrial policy, but that’s only because many of their costs are off budget.

Or to put it another way, if you think promoting manufacturing with subsidies is too expensive, you should definitely be against tariffs, which are actually even more expensive.

And you know who did try to boost manufacturing with targeted subsides, and had a lot of success? The Biden administration:

Biden also pursued quite tough policies against China that, unlike Trump’s, didn’t punish our own economy at least as much as they punished China’s.

Look, I know that many Democrats are pissed at Biden for not stepping aside sooner. But that shouldn’t mean disavowing the good his administration’s policies did.

When Bernie Sanders declares that Democrats abandoned the working class, he’s trashing his allies and playing into Trump’s hands: The Biden administration was the most pro-worker government we’ve had since the New Deal, and while Obama was more cautious, he rescued the auto industry, greatly expanded health coverage, and significantly raised taxes on the rich. Why do you think Wall Street hated him?

Should tariffs ever be part of an industrial strategy? The only justifications are political. As it happens, U.S. law makes it much easier to impose tariffs than to provide subsidies: Tariffs can be raised through executive action, while subsidies require legislation. This means that there are some circumstances, such as responding to sudden import surges, when tariffs may be the only available recourse.

It’s also true that imposing indirect costs on Americans via higher prices sometimes flies under voters’ radar, while direct outlays are more visible. But do we really want to use tariffs to pursue industrial policy because we think voters won’t notice the cost? That may not even work politically now that Trump has raised voters’ consciousness on the issue.

So Democrats don’t have to be purists who rule out all tariffs. But they can and should say that tariffs are not how you build a better economy.

And if the goal is to build a better economy, policy should focus on creating good jobs everywhere, not fetishize manufacturing,

Good jobs don’t have to be in manufacturing, and manufacturing jobs aren’t always good

“McDonald’s workers in Denmark are paid more than Honda workers in Alabama.” That claim has been showing up in my inbox, so I checked it out. And it’s true. McDonald’s workers in Denmark are paid more than $20 an hour, in addition to receiving substantial benefits. Indeed.com says that “production associates” at Honda’s Alabama plants are paid an average of $14 an hour.

What this comparison tells us is that institutions that empower workers are more important in determining workers’ pay than what sector they work in. Two-thirds of Danish workers are represented by unions, while auto workers in Alabama aren’t unionized. Empowering service sector workers can make their jobs good; disempowering manufacturing workers can make their jobs bad.

There’s a lot of romanticism about what manufacturing jobs in America used to be like. It’s true that some industrial workers were well paid. But that was mainly because they had strong unions. Nonunionized workers in, say, South Carolina’s textile industry had low pay and terrible working conditions. Many came down with brown lung disease caused by breathing in lint. Why should we want to bring those jobs back?

And even in America, where many service-sector jobs pay poorly, there are also many jobs outside manufacturing that offer good wages. Employment in health care now greatly exceeds employment in manufacturing; well, according to Pew, 55 percent of health care jobs provide middle-class incomes. And policies that increase workers’ bargaining power could greatly expand the number of good jobs outside manufacturing.

The point is that Democrats shouldn’t engage in Trumpian nostalgia for an industrial era that isn’t coming back. They should be pushing for policies that will make jobs better in the 21st century, not harken back to a rose-colored vision of America in 1955.

And they should never, ever say that Trump’s tariffs have a point. Because they don’t.

MUSICAL CODA

Short and sweet — exactly!

“So Democrats don’t have to be purists who rule out all tariffs. But they can and should say that tariffs are not how you build a better economy.”

Trump and tariffs is like a little kid with a hammer. He doesn’t know what he’s doing but he’s having fun banging away at everything in sight.

And there’s zero adult supervision in this administration.