The tech bros who helped put Trump back in power expect many favors in return; one of the more interesting is their demand that the government intervene to guarantee crypto players the right to a checking account, stopping the “debanking” they claim has hit many of their friends.

The hypocrisy here is thick enough to cut with a knife. If you go back to the 2008 white paper by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto that gave rise to Bitcoin, its main argument was that we needed to replace checking accounts with blockchain-based payments because you can’t trust banks; crypto promoters also tend to preach libertarianism, touting crypto as a way to escape government tyranny. Now we have crypto boosters demanding that the evil government force the evil banks to let them have conventional checking accounts.

What’s going on here? Elon Musk, Marc Andreesen and others claim that there’s a deep state conspiracy to undermine crypto, because of course they do. But the real reason banks don’t want to be financially connected to crypto is that they believe, with good reason, that to the extent that cryptocurrencies are used for anything besides speculation, much of that activity is criminal — and they don’t want to be accused of acting as accessories.

But let’s back up a bit and talk about fundamentals.

One of the (many) odd things about cryptocurrency is that it has somehow managed to maintain an image as something futuristic when it’s actually ancient in tech years: Bitcoin, the original cryptocurrency, which still accounts for more than half of the total crypto market cap, is 15 years old. Over this entire period, monetary economists and banking veterans have asked, what’s this for? What legitimate use cases are there for cryptocurrency that can’t be served more easily without the blockchain rigamarole?

I’ve been in many meetings where this question has been raised, and have never heard a coherent answer. In fact, crypto has made essentially no inroads on conventional money’s role as a means of payment — which is why crypto guys are so angry about being debanked: you can’t do business without an account at one of those banks Bitcoin was supposed to replace. Even the crypto industry’s own employees won’t accept payment in crypto, which is why the failure of Silicon Valley Bank, where they deposited funds for payroll, was an existential crisis demanding, yes, a government bailout.

Yet Bitcoin has hit $100,000 and cryptocurrency assets have a combined value of $4 trillion. What’s going on?

One answer you sometimes hear, especially from financial executives who want to say something positive about crypto, is that Bitcoin in particular may be turning into the digital equivalent of gold. After all, gold doesn’t really function as money — try buying a car with gold bars — and its industrial and dental uses, while real, don’t remotely justify its value. It’s just an asset that people consider valuable because others consider it valuable, and it has maintained that status even though gold coins went out of use as a means of payment generations ago.

Another answer is that it’s all speculation or gambling (sometimes it’s hard to tell the difference), largely driven by testosterone. A Pew survey found that 42 percent of men 18-29 (versus 17 percent of women) have invested in, traded or used cryptocurrency, even though it’s extremely hard to use in ordinary life — the car dealer who won’t accept gold bars probably won’t accept Bitcoin either. The surge in crypto has gone hand in hand with a surge in meme stocks like GameStop and political bets, not to mention an enormous and worrying surge in sports betting:

But there’s a third possible explanation of crypto’s rise. Maybe asking “what are the legitimate use cases for this stuff” is the wrong question. What about the illegitimate uses, ranging from tax evasion to blackmail to money laundering? Maybe crypto isn’t digital gold, but digital Benjamins — the $100 bills that play a huge role in illegal activity around the world.

The old adage says that crime doesn’t pay, but of course it does in many cases. And it needs a means of payment, preferably one that isn’t too easily tracked by law enforcement. Traditionally, and to a large extent even today, that has mostly meant large-denomination banknotes.

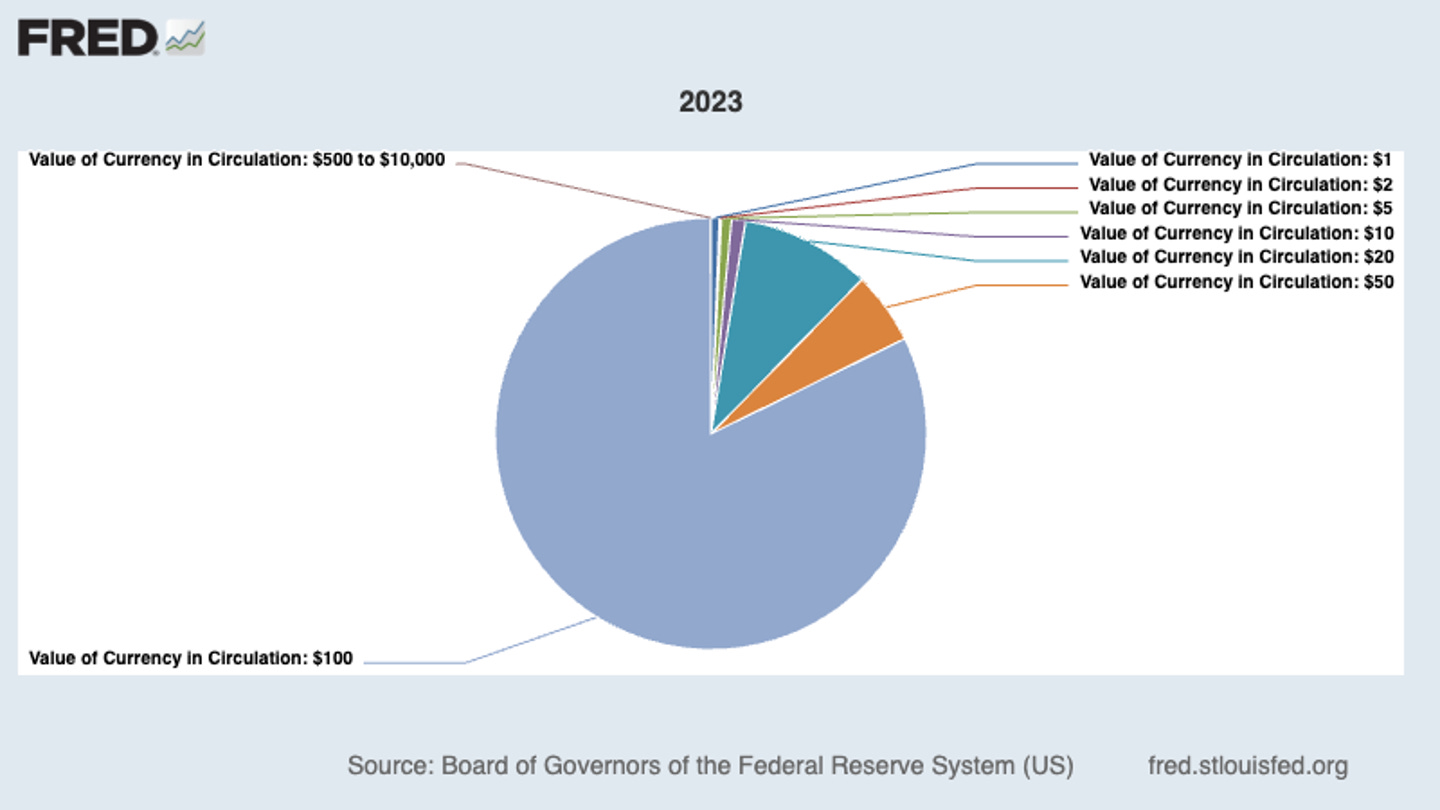

I don’t know how many people know this, but the great bulk of U.S. currency in circulation, at least in terms of value, consists of $100 bills:

Most people can go a whole year without ever seeing a $100 bill — yet there are roughly 60 such bills in circulation for every man, woman and child in America. Who’s holding them? Well, indirect evidence suggests that they’re mostly being held outside the country. And while getting a precise number is almost by definition impossible, there’s no real doubt that many and probably most of the Benjamins out there are being held for illicit purposes. That’s why some prominent economists, notably Ken Rogoff, have called for completely phasing out large-denomination notes.

But while the sheer value of $100 bills in circulation suggests that there are still plenty of tax evaders and drug dealers with safes full of cash, banknotes are an awkward medium for really large-scale criminal activity. True, $1 million in $100 bills only weighs 22 pounds; but a million isn’t that much money nowadays. When Bashar al-Assad sent $250 million to Moscow in the form of $100 and 500-euro notes, the cargo weighed two tons.

Enter crypto. British authorities recently broke up a big money-laundering scheme involving exactly the villains you’d expect:

Presumably not everyone in crypto is participating, even unknowingly, in criminal activity. But the use of crypto for money laundering appears to be rising rapidly. And if I were running a bank, I’d be reluctant to host a bank account belonging to someone who might be involved in unsavory activities.

You might think that this was my right. Aren’t banks private companies, who can choose which customers they want to serve? OK, we have laws against discrimination based on race or gender, but civil rights for crypto bros sounds like a stretch.

Or maybe not. Howard Lutnick, Trump’s choice for Commerce secretary, has close ties to Tether, the company that is at the heart of the scheme the UK just uncovered and is rumored to play a large role in money laundering in general.

We’ll see what happens. But what Musk and Andreesen are demanding could be seen as a call for the U.S. government to intervene to make life easier for criminals. And if you think such a thing would be inconceivable under the second Trump administration, you haven’t been paying attention.

MUSICAL CODA

Thanks Paul. Kamala Harris was able to raise $1 billion with mostly small donors for her campaign. But that was laughable compared to the dark money of the opposition. Stock manipulation by DJT and crypto schemes I suspect allowed Trump and MAGA to rake in many billions in bribes from foreign entities and South African billionaires who will expect their pound of flesh.

Bitcoin allows retail investors to invest in the black market economy.